This was written in March 2019. Content note: Christchurch terror attack, descriptions of sickness.

It started with vomit, then bile. The ambulance was called, but I couldn’t walk, so they called the fire service to carry me down the stairs. They strapped me into a chair and I closed my eyes against the bright sunlight. I tried to raise a hand to shield my eyes from it – my eyelids were insufficient – but my hands were strapped down. That was the last thing I remember until I woke up surrounded by doctors and machines.

In hospital, when they asked my name, I answered. My address, the year, the month, the day. Wednesday, I whispered. It takes more energy than you realise, to move your lips, have the sound come out. Yes, there’s pain – in my throat, in my abdomen, in my head. No, I don’t know what happened, I woke up at 1am and I was sick. I thought perhaps I could just be sick like a normal person, but I was sick like someone familiar with the inside of an ambulance. The ambulance my brother called because I was barely conscious at 10am. I was waking up only to throw up, and falling asleep immediately with my arm wrapped around the sick bowl, incapable of putting it on the floor. Caspian got himself off to school after making his own breakfast and lunch and begging to stay home to look after me. I was conscious enough at that point to deny the request and insist he go to school.

In the ward, there’s Janet. Janet wants to die. She doesn’t say much, at least not clearly, but she says that. They let her take the CPAP mask off to talk to the doctors, and she moans a little less. Delirious, they say, and I think: delirious? Have you heard her moan? A few minutes in the ward is enough to be clear she is in agony. She groans and whimpers through the night and begs them to stop treating her. No one comes to visit but her husband calls to check in.

Eating is painful and that sweet ‘n sour pork isn’t worth it. They convince me to have a lemonade Popsicle and I manage half, and leave the rest to melt on top of the vegetable soup. When Caspian comes in he sees the pottle of soup and asks if it’s puke. My brother and I laugh but it’s a reasonable question, under the circumstances.

Caspian is less worried, he says, after seeing me in hospital. As wrecked as I must look, at least I’m conscious and no longer vomiting, I suppose.

I’m moved from the high dependency bay to Ward 5 South, bed 8. It takes me a few hours to get used to not having a nurse at the end of my bed, attentive to my every whimper. Which is a strange thing to get used to in the first place. The diabetes nurse comes in and tells me nothing I don’t already know. His sleuthing gets no further than mine – what triggered this? Inconclusive. My flatmate messages to say she was feeling unwell that night too and I conclude we may have both had a virus, but she went to work the next day and I went to the Emergency Department.

Then, there’s Erika. Erika thinks I may be her daughter come to visit, hiding behind the curtain between bed 7 and bed 8, so every now and then her carers let her peep into my half of the room, to prove I am not her daughter. She comes and puts a magazine in the sink at the end of my bed. Erika gets very confused, so she has someone with her 24/7. Yesterday there was Charlie, who kindly called her “my love,” and once emptied my sick bucket, though he wasn’t there to look after me.

I can still hear Janet moaning occasionally from down the hall. Someone else is wailing in pain. I don’t know if it is physical pain or grief pain but it sounds more like grief to me. It’s late at night and now that I’m recovered enough to be aware of my surroundings I just want to be home. I don’t want to listen to Janet’s moans, to those wails of grief, to Erika’s confusion, to the man earlier who was shouting “you motherfucking cunt, you motherfucking cunt,” spitting the words at someone likely undeserving. Their hurts are all worse than mine, but mine is still fresh.

My diabetes is quickly brought under control. You can go home later or tomorrow, they say. Ok good, I say, but… I think there’s something wrong with my feet. I can’t move them properly. The doctor does some tests. She brings a neurologist in. He does some more tests. I can’t walk properly.

WHY CAN’T I WALK PROPERLY?

There are two possibilities, the neurologist says. One: insulin neuritis, a temporary neuropathy response to the high doses of insulin that I needed on admission. Two: Guillain-Barré syndrome. The only way to tell is to wait and see if it gets worse. I’m trying not to feel sorry for myself but I am sick and alone and worried. I live up 50 stairs, I have a child, my life is hard enough, I need to be able to walk. There is so much wrong with my body already. I say this to my brother and he nods – it’s not fair. He has perfect health; I have two chronic illnesses, a cognitive disorder, and am rather susceptible to depression.

Then I open Facebook to see that a friend marked herself safe during the “Christchurch attack.” The what? I Google for an answer, but I don’t have the energy to fully understand and react to the horror of the massacre that’s just happened, so I just read. Fifty Muslims shot dead during prayer, including a four year old. Many more injured. The man who greeted the white supremacist shooter at the door of the mosque, saying, “come in, brother.” I don’t know how to process this. This happened here? In New Zealand?

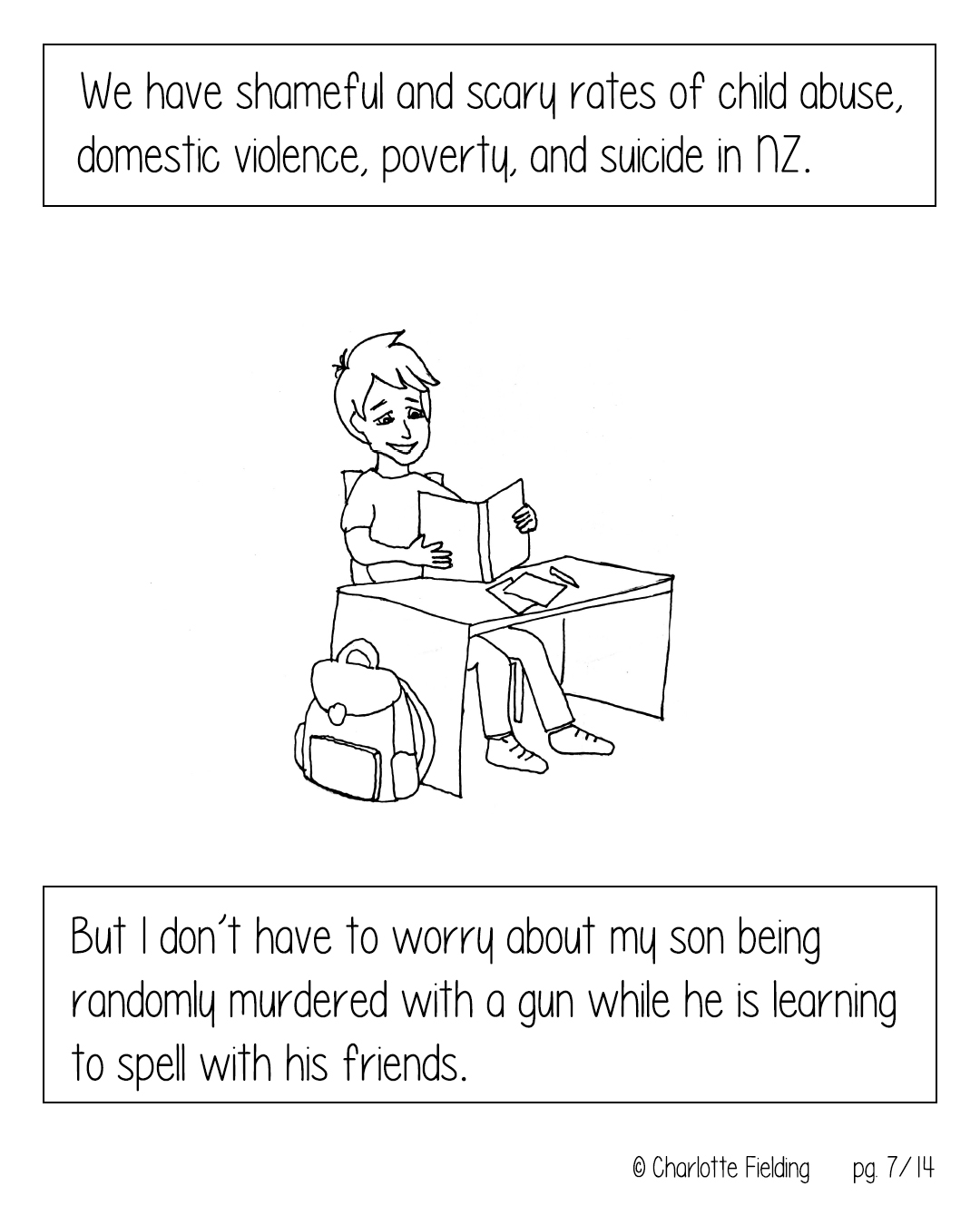

The lack of nerve control in my feet doesn’t get worse, so the neurologist says I should be ok to go home. My foot is still weird and a bit floppy but if I concentrate I can walk. I ask if I can get out on Sunday, to watch Caspian do the Weetbix Tryathlon. I’m not sure how I’ll walk from the car across the field to watch him, but I will, somehow. It’s his birthday on Monday, too. I can’t let him down by being absent, even if I was near death a few days earlier. The Tryathlon ends up being cancelled anyway, like many other large public events around the country, in the wake of the Christchurch massacre.

I want to attend the vigil on Sunday after I get out, but on Saturday night Erika doesn’t sleep, which means I don’t either. “I WANT my WATCH,” she’d say, getting up and turning the lights on. “Erika, it’s time for bed,” her carer would say. “Don’t TOUCH my LEGS,” says Erika. Twice she comes to sit in the chair on my side, watching me in bed. I lie awake, missing Caspian, exhausted, confused.

I don’t make it to the vigil – how could I have thought I would? – but I do make it home, after discharging myself. I know I need more rest and care but I need to be home with my son more. I’m relieved, and I’m devastated, thinking of all the people in Christchurch who won’t ever go home.

Several days later, I’m watching Caspian learn how to cross his arms while skipping rope. He is determined to do it – jump, cross arms, jump, uncross arms, jump – and is soon dripping sweat despite stripping down to his underpants. For a few years now he has regularly queried the strength of my love for him by asking some form of this question: how much suffering would I put myself through to save him? Would I break my leg to save him? Would I run a hundred kilometres to save him? Would I die to save him? I repeatedly assure him there is no limit to what I would do to save him, so could we stop discussing it because it’s getting a bit ridiculous. Like, “would you poop on your own arm to save me?”

Tonight he says he would skip rope a million times to save me. Play the game, he says. I push aside the knowledge that this is likely to deteriorate fast, because I can tell he needs it to play out. So I pretend I’m in some way about to die: oh no! Save me Caspian! You have to keep skipping, don’t stop. He starts yelling as he’s jumping: I’ll save my mum! I don’t want my mum to die. I’m not going to let you die, Mum, don’t worry. I’ll save you. I DON’T WANT MY MOTHER TO DIE.

THAT’S THE ONLY THING I WANT IS FOR MY MUM TO NOT DIE.

He collapses on the ground – in anger or terror or relief, I can’t tell – and I thank him for saving me. It’s not until hours later, the scene replaying in my head as he lies asleep and calm, snuggled up next to me, that I realise what it was about. He doesn’t want his mother to die. His processing of seeing me so ill finally made its way outwards. He found a way to scream about it. And all he has to do, is something. Skip rope one million times.